« From Hotel to City Hall | Main | Suomenlinna »

June 29, 2006

Conference call

The Monk is away to Cincinnati for a conference at which he is giving the paper in the extended post below. The conference is to be attended by fire investigators from all over the world and drawn from all sorts of disciplines. These conferences are a great way to exchange ideas and thinking on a range of issues, some seemingly unimportant, and others giving that "eureka" moment as something not previously considered, or perhaps only vaguely understood becomes clear.

You can visit the conference website through the National Association of Fire Investgators site. Look for the link labelled ISFI 2006.

TRAINING IN FIRE INVESTIGATION

International Symposium on Fire Investigation

University of Cincinnati

Cincinnati

June 2006

THE LEGAL POSITION OF FRS FIRE INVESTIGATORS

Until recently the UK Fire and Rescue Services had no powers to conduct an investigation into the origin, cause or progression of a fire. Such investigations were done, but they were dependent upon a “good will” working arrangement with the occupier of the affected premises and the service. Not unnaturally this could create a problem if the investigator was denied entry or challenged on his or her findings and report, particularly as, until recently, a misleading Circular reiterated the false impression that the fire officer could not be considered an “expert”. As the final conclusion on any report is inevitably an opinion – albeit one supported by the facts and information discovered during an examination of the scene of the incident – this “advice” from the relevant Department of State (currently the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister) could be, and has been, used by defence attorneys to get cases dismissed from court. In British legal precedence only an acknowledged “expert” may give “opinion” in evidence, and, if the “expert” is a fire officer, and the case hinges upon his or her “opinion” their exclusion as an “expert” can, and does, have serious consequences.

The situation vis á vis the status of “expert” witness is a complex one, but, in any court in the UK, it is for the judge to determine who is and who is not an “expert” witness. Such decisions are always based upon several criteria, usually a consideration of experience, qualification and credibility in any individual. It is further complicated by the degree to which a witness can be regarded as being “expert”. An expert in the UK legal system is someone who is considered to have a wider than usual knowledge in a particular subject. Thus, an amateur can be declared by the judge to have an expert knowledge of a particular subject and be regarded as more credible than, say, a professional in the same field. This has happened in a case where an amateur student in the field of handwriting was declared in a court to have a greater grasp of the subject than another expert who had less specific experience and knowledge. This “confusion” of advice from a government department has certainly not helped the professional fire officers who must daily complete a report form on incidents which require them to complete a section which states “Supposed cause of fire” – clearly an opinion and certainly one which may lead to further investigation and possibly legal proceedings.

For those who are recognised as national or international “experts”, there is the privilege of being allowed to sit in court during the hearing of testimony from all other witnesses, for the “expert” witness recognised only in that court, this privilege is not available and the witness must wait outside the court until after having given his evidence-in-chief and been cross examined. He or she may then sit in the court to hear the remaining witnesses and experts give their evidence. That said, the status of the Fire Service Investigator remains something of a dichotomy, as the majority do not normally fall into the category of “Court Expert” in the fullest sense of that definition. There are, however, processes in place whereby a Fire and Rescue Service Investigator may, by a process of peer review, registration and qualifications become such an expert.

A special body has been established in the UK as the Council for the Registration of Forensic Practioners, and a suitably experienced and qualified fire service investigator who meets the criteria may make an application to this body for registration. To do this requires the submission of a body or work for peer review, a full curriculum vitae and a review of both qualification and experience. It is, rightly, a rigorous process and registration is not lightly given. Once registered a candidate is subject to regular peer review and may be struck from the register if they can be shown to have failed to follow proper scientific and forensic procedures or to have become “incompetent” as an “expert”. While, as I have already explained, it is for the court to determine whether or not to “recognise” an “expert”, those who are on the Register are more likely to be granted the full status than someone who is not.

The legal position of the fire and rescue service investigators in the UK changed with the receipt of the Royal Assent of the Fire and Rescue Services Act 2004. A new power was created which gives an “Authorised” officer the power to investigate the cause of a fire or why it progressed in a particular way. This set out in the Fire and Rescue Services Act 2004, Section 45 (1)(b) and subsequent clauses qualify this and provide certain additional powers, in particular those provided in Section 46 which make provision for the taking of evidence and for taking “other persons” into the investigation scene.

The provision of legal powers to carry out investigations places an “implied” legal duty upon the service to use these powers and it further implies that they must conduct any investigation in a thoroughly professional and scientific manner. To this end, a series of analyses of the actual roles and expertise required to do this have been conducted and the resulting “Role Map” was then used to determine the knowledge and skills development requirements for those wishing to become competent in the field of fire investigation. These criteria were then used to develop what is the now adopted National Occupational Standard. This has helped enormously in focussing on what fire investigators need to be able to do, to understand and to report in order to be deemed “competent” to do this important task. There are, inevitably parallels with the NFPA 1033 and certainly the systematic approaches set out in NFPA 921 have a powerful influence on the conduct of investigations.

As a part of this, the service has had to learn to work in partnership with the Police Forces and to work to the same rules and standards of evidence. Necessarily this involves working to the parameters of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act and related legislation which sets out the requirements for criminal evidence. In practice these have much the same effect as the celebrated Daubert Rules in the US since they require that all evidence is managed in a way that ensured fairness and legitimate access for the defendant.

But the position is complicated by the fact that they are specifically barred from entering, as of right, any premises occupied as a dwelling unless they have fulfilled one of the following criteria:

24 hours notice has been given in writing that they intend to carry out the investigation, A warrant to enter the premises for the purposes of conducting an investigation has been issued by a Magistrate, or The occupier has waived his or her right to receiving notice and consented to the Fire and Rescue Service Officer entering and conducting the investigation immediately.

Section 45(3) of the Act states:

(3) An authorise officer may not under subsection (1) –

- enter premises by force, or

- demand admission as of right to premises occupied as a private dwelling unless 24 hours notice in writing has been has first been given to the occupier of the dwelling

This is further compounded by the restriction in subsection (4) –

(4) An authorised officer may not under subsection (1)(b) enter as of right premises in which there has been a fire if –

- the premises are unoccupied, and

- The premises were occupied as a private dwelling immediately before the fire,

Unless 24 hours notice has been given to the person who was the occupier of the dwelling immediately before the fire.

In the United Kingdom the Police are solely responsible to the investigation of any criminal activity. Thus their powers are focussed upon preventing crime, investigating crime and assembling the information for the prosecution of the perpetrators of crime. There are certain limits upon these powers, for example, police officers may enter a building in which a crime is believed to be in progress in order to apprehend the criminal(s), they may enter a building in which a crime has been committed to investigate that crime (provided the victim invites them to do so) or they may enter a building in execution of a warrant issued by a court. These are termed “general” powers and do not permit the police officer to override a specific restriction on any other bodies powers. Thus, where the Fire and Rescue Service officer is required by the statute to give notice of his or her intention to investigate, this cannot be overridden by the police officer using their power of entry to “invite” the fire and rescue service to accompany them.

The legal “bars” placed on the power of entry to investigate fires mean that the fire and rescue service and the police services have to put in place policies and procedures for those occasions where a joint approach is required. Ad hoc arrangements will simply lay both sides open to attack by the defendant’s legal team in any court and the prosecutions case may be jeopardised by this. Thus, it is vitally important that the procedures have legal credibility and are robust enough to withstand scrutiny in the cold light of the court room.

The Fire and Rescue Service investigator must, in exercising his powers to investigate also keep in mind two very important aspects in regard to the investigative process. First, if it is a crime scene, or is potentially a crime scene, the police have the overriding authority and their lead must be followed. The FRS cannot and must not, undertake activities which could lead to a criminal investigation being obstructed or in anyway compromised. Secondly, the process of investigation where there is a possibility that some form of enforcement action, for instance in the case of an offence being committed under the Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order 2005, and for which the FRS are the enforcing authority, must be conducted in accordance with the rules determined by the Police and Criminal Evidence Act, the Criminal Justice Act and the Criminal Procedure and Investigations Act. All of these contain restrictions or procedural requirements intended to ensure that the rights of the individual are not in any way compromised or that a miscarriage of justice occurs.

The Fire Investigator is therefore required to be familiar with the procedures set out in Code B of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1988 which sets out the requirements for the collection, collation and control of evidence. They must also adhere to the procedures for interviewing witnesses, recording of interviews either on paper (which requires a verbatim record) or by means of electronic devices. Everything done during the investigation should be recorded in a “Contemporaneous Note” and these must be kept in a particular style and format. A simple “aide memoir” provides a useful guide on this and is based on a simple “Acrostic” –

There shall be NO:

Erasures,

Lines missed,

Blank spaces,

Overwriting, and

Written in INK, with

Spare pages struck through!

The notes must be dated and signed and the note book itself must have consecutively numbered pages. Where a unique note book is used for each case, the books must have a unique identifying number on the cover and a register kept of who they were issued too and for what purpose or case. Failure to follow these simple rules will usually result in the court refusing to allow an investigator to use his note book as an aide memoir in the witness stand – usually with embarrassing results! This is neatly summed up in Section 139 of the Criminal Justice Act 2003 which creates a presumption in favour of a witness in criminal proceedings refreshing memory from a document whilst giving evidence provided that:

He/she states that the document represents his or her recollection at the time he or she made it; and The witness’s recollection was likely to be significantly better at the time the document was made (or verified).

The fact that the witness may read the statement he/she may have made at the time of the investigation or given to another investigating authority prior to giving evidence does not affect this presumption. This is a well established principle in the UK and one which the courts guard rigorously, taking a very strict view on the acceptability of note books as a result.

Interviews conducted by the investigator must also follow the strict guidelines set out in PACE Code C, creating another training aspect for the would be investigator. Code C provides a definition of “Interviews” which makes a distinction between a conversation with someone who may impart certain information, and an interview conducted under caution and along formal guidelines, it is: -

“An interview is the questioning of a person regarding his involvement or suspected involvement in a criminal offence or offences which, by virtue of paragraph 10.1 of Code C, is required to be carried out under caution”.

It means in essence that any interview conducted under these rules and in a formal way has to be done using a technique referred to a “Cognitive Interviewing”. This ensures that the interviewer cannot be accused of “leading” a witness or “putting words in the witness’ mouth”. Such interviews should always be conducted with one person recording the interview and the other asking the questions. The technique is one which requires careful thought and a little planning. It also requires very good listening skills and an ability to recall things said which require further expansion and lead to secondary questions.

The “Caution” referred to in PACE is one which has to be administered whenever a person is under suspicion of having committed an offence, but, for the most part, in any fire investigation, it will not be used or administered by the fire officer. The crime of arson (Willful Fire Raising in Scotland!) is an offence which falls within the ambit of the Police and they will therefore always be the authority who will administer the caution and conduct the interview.

The next item which is of considerable importance in developing good investigative practice for fire personnel is the importance of recognising control of entry to premises and the control of gathering and collating items in evidence. “Contamination” of evidence through lax control or carelessness, whether through ignorance or bad management, is viewed by courts to be inexcusable, and the investigator needs to know and understand the rules governing this aspect of the investigative process very well.

PACE Code B deals specifically with the Seizure of Articles and Substances and reference to both the Fire and Rescue Services Act 2004 Section 46 and to the Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order 2005 give the Fire and Rescue Service certain powers to seize and examine items – an activity which clearly falls under the aegis of Code B! Thus, the fire investigator needs to be aware of the process for collecting samples, for recording them properly and ensuring that they are secured and packaged in a manner which preserves the integrity of the item. This poses a further serious question, one of control and of managing the storage of any such items, as these must be retained in a secure facility under continuous control and be available for examination by an officer of any court, or the defence and other interested parties.

In a rather interesting way, the Fire and Rescue Service officer who exercises any enforcement powers is also incorporated into another Act aimed at regulating the powers and the use of powers for the police when it comes to surveillance. The Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act, referred to as RIPA, allows the fire and rescue services to access certain restricted information sources, but to do so, they must appoint a person or persons as “SPoC” – not the famous Vulcan – but a Single Point of Contact person through whom all requests must be channelled. The Act also makes clear that certain activities, such as “staking out” premises, by, for example, booking into a hotel in order to check certain management compliances with regulations, constitutes a “controlled” activity for which permission must be obtained prior to commencement of the surveillance.

THE NATIONAL OCCUPATIONAL STANDARDS

The National Occupational Standards have been drawn up in an effort to identify all the knowledge and skills necessary for competence in the field of fire investigation. These standards were the work of a committee of fire investigation practioners and an expert in the development of National Occupational Standards, and were designed to be broad enough to embrace all levels of investigation and all the various disciplines involved. This is a comprehensive approach, but it is also intended to describe the knowledge, skills and functions required for ALL fire investigators, police, fire and other agencies and independent operators. It spans the three “levels” identified in preliminary work on developing these so that the UK’s investigators fall into one of three groups.

With such a broad brush approach, the interpretation of the NOS is key to determining the appropriate training required at each level. It will also be recognised that the vast majority of Fire and Rescue Service personnel operate at Level 1, with a number at Level 2 and a very small number able to qualify for recognition at Level 3. As mentioned in the opening paragraphs of this paper, the courts determine the status of individual witnesses as “expert” or not and this determination is based on the individuals qualifications, depth of knowledge and experience and credibility. Recent unfortunate miscarriages of justice in cases where conviction was based almost entirely on “Expert Opinion” have made courts extremely wary in this regard and the fire investigator is no exception to this. Thus, anyone who seeks to be recognised as an “expert” in the field of fire investigation is required to undergo a rigorous registration process which requires the submission of evidence of qualification, assessment of skill in applying knowledge and technique and a peer review of cases investigated. This will permit their being eventually recognised by being placed on a register of Forensic Practioners managed by the Council for the Registration of Forensic Practioners (CRFP) and to regular review of their competence in the field. The Council manages the registration of a wide range of forensic groups, each embracing a specific forensic discipline, so a person thus registered is not unnaturally registered to a particular field and does not become “expert” in any other discipline unless specifically so registered.

For personnel in the Fire and Rescue Services, the National Occupational Standard can be broken down into individual “modules” for the purposes of personnel development, allowing a mixture of training, learning and qualification approaches to be adopted. These Modules provide four Knowledge/Skills groups which cover: -

Planning for Fire or Explosion Investigation, Investigate the origin and cause of a fire Analyse the findings and respond to the findings of an investigation, and Report the findings at formal proceedings.

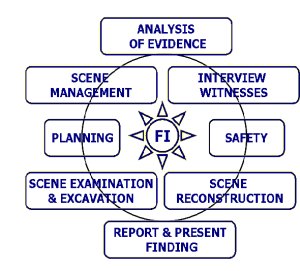

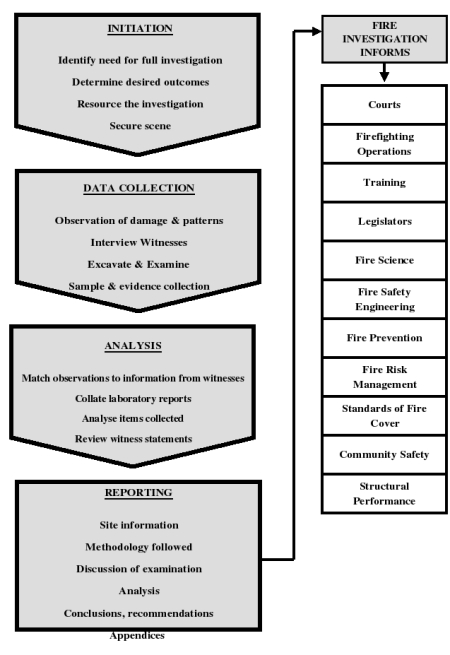

A graphic representation of the elements required for a structured fire investigation and the areas in which competence is required to be achieved.

These somewhat vague categories encompass a wide range of activity falling broadly into a knowledgebase acquisition covering: -

Fire science, including the physics and chemistry of fire, fire spread and behaviour and related matters, Fuels, inhibitors and ignition sources, Structures, structural materials and their behaviour in fire, Data collection techniques, Investigation procedures including scene management, access control and record keeping, Analysis methods and tools including the use of computer modelling, Burn pattern analysis, Evidence collection and controls, Fire pathology, DNA evidence and procedures for avoiding contamination of this, Interviewing techniques and procedures, and Legal authority, restrictions and controls.

Naturally, there may also be a need to understand, if not to actually carry out, the processes by which laboratory analysis may be conducted. There will certainly be a need to understand what, if anything, can be achieved by forensic chemists and what they will not be able to provide. At all levels there will be a need to understand and to be able to carry out simple experiments and research to find additional information about the behaviour of materials or fuels which may throw further light on something found in the course of a scene examination.

That said, the difficulty for those designing training for all personnel who may be required to conduct a fire investigation in one form or another and at any given level, is how much information is essential and what can safely be assumed to be “prior learning” knowledge.

Thus, at the Level 1, the training development may include some electronic learning, some classroom based learning, mentoring and peer guidance and accreditation of knowledge gained on other programmes. At Level 2, this needs to be expanded and focussed on a broader platform providing again, a mixed learning approach which takes account of transferable knowledge, experience and practical and classroom acquired knowledge and skills to bring personnel up to the threshold levels of competence.

Those aspiring to become Level 3 Investigators need to undertake a Degree level programme to underscore their knowledge base (although this can be achieved by other means) and this must then be balanced against experience on the ground, peer review of submitted work and performance under cross examination in court. Successful candidates may then be registered through a body called the Council for the Registration of Forensic Practitioners (CRFP) and may then be considered by the Courts as “recognised” experts.

As originally envisaged by the Training Sub-group of the Arson Control Forum, the “levels” where broadly defined as being: -

Level 1 – any person in the FRS who was required to complete a Fire Damage Report and record a “Supposed Cause of Fire”. Level 2 – a specialist investigator from the FRS and possibly from an Insurance company or other “non-Forensic” discipline with a wide range of experience and some qualification who may or may not have been a recognised “expert”, and Level 3 – a Forensic Investigator who specialises in investigating fires and explosions and who is an acknowledged Court “Expert” who has either a Post Graduate Degree or Doctorate and specialist knowledge in a particular aspect of such investigations.

Subsequent development by the Chief Fire Officers Association (CFOA) special interest Task Group on Arson Reduction and Fire Investigation has placed a broader interpretation upon these and currently envisages the levels as:

Level 1 – Fire and Rescue Service personnel whose role includes Incident Command and requires them to complete a report referred to as an “FDR 1” or an “FDR 3” both of which require completion of a section headed “Supposed Cause of Fire”, Level 2 – FRS and Police Crime Scene Managers/Investigators who are required to investigate fires which involve a fatality, a criminal act, a fire of special or unusual interest or where the Level 1 investigator has been unable to identify a cause, and Level 3 – which involves FRS Investigators, Forensic Scientists, Police and other Specialist Investigation Agencies. These will include persons who are recognised “Expert Witnesses” in their field under the UK legal system.

This has somewhat muddied the waters as far as the original intent was concerned, but does provide a useful platform from which personnel can plan their career development requirements. It is also helpful in terms of identifying the “start-up” level for individuals coming into the field from outside the Fire and Rescue Services since it makes clear that Level 1 is a basic level for form filling purposes only. The key area is obviously, for the majority of those wishing to gain a specialist role, in Level 2.

With the advent of the registration process, many senior FRS investigators are now looking to become Level 3 investigators and have undertaken Masters Degree studies in order to develop their knowledge base appropriately. This, taken with prior training and their experience in the field enables them to apply for registration, and, subject to the court’s recognising this, to be acknowledged as Expert Witness. Naturally, the number of FRS personnel who reach these exalted heights will necessarily be restricted since many will not have the opportunity to build a sufficiently broad portfolio for registration.

THE TRAINING PROGRAMMES

The training programmes available to would be UK fire investigators are available from a number of providers. These range from one and two day “awareness” programmes to one, two and even three week courses which provide a mixture of theoretical knowledge development and practical skills in examining a fire scene. Several providers now deliver programmes broken down into Introductory”, “Foundation” and “Practical” usually of about a weeks duration at least for the last two programmes. Some offer “Advanced” courses as a follow on from their initial progression and several offer “Maintenance” courses for those who need to renew or refresh their skills after a period of relative inactivity in the field. All such programmes are based on the requirements set out in the National Occupational Standards and this means, in effect, that they also cover the requirements for NFPA 1033 in so far as that standard is applicable to the UK situation.

Raising the awareness of the importance of noting the state of the fire and the vehicle or structure at the point of arrival – and then ensuring that, while effectively extinguishing the fire, the scene is preserved as far as possible, is an important element in developing Level 1 candidates. (Photograph © P G Cox 2006)

For the majority of Fire and Rescue Service personnel, their personal development in this discipline will begin with a Fire Investigation and Forensic Awareness programme provided usually “in Service” either by the particular Service’s own FI Team or by an outside provider. This is usually aimed at Crew and Watch Managers and is aimed at developing their ability to identify the point of origin in a relatively uncomplicated scene, and thereby the cause, or in recognising a scene where a higher level of investigation will be required and to preserve as much as possible of the potential evidence it contains. They will receive advice on how to prevent the loss of evidence, on DNA contamination and how to secure and preserve the scene as far as possible.

As with a vehicle, the Level 1 candidate needs to recognise the importance of being able to recall and interpret the state of the fire at the moment of arrival and to preserve as much as possible of any external evidence which may assist in prosecuting a criminal at a later stage. (Photo © P G Cox 2006)

Such a programme typically covers:

Legal authority, restraints and restrictions, Identifying a point of origin and likely cause, Electrical causes of fire, Data collection and information gathering, Scene management and preservation, Scene examination, pattern analysis and evidence interpretation, Forensic awareness and preservation of evidence, Restrictions and triggers for higher level investigation, and Hand over procedures and information exchange.

Such a programme is usually run over two days as a minimum and would include some practical and “table top” exercises in simple evidence analysis and examination. It should be said that Health and Safety issues form a large part of the National Occupational Standards in Fire Investigation, but as this is an integral part of most fire and rescue service officers “mainstream” development, it is generally covered in the form of “reminder” and “refresher” elements within the appropriate sessions in any programme of this duration. Not unnaturally there needs to be an element of skill and knowledge assessment attached to the programme and this can take several forms, although a mixture of practical assessment in the workplace coupled with a form of knowledge testing is often required to show the individual has developed the necessary ability and is ready to begin the next stage of development.

Ideally, candidates would be able to examine a real scene in training, but table top exercises using good photographs which adequately illustrate the learning points can be as effective. (Photo © P G Cox 2006)

Equally valuable is allowing candidates to examine real artefacts and requiring them to answer questions or a series of questions concerning the item or the state of it. (Photo © P G Cox 2006)

For the Level 2 practitioner, the development programmes build upon their foundation knowledge of fire behaviour and fire fighting, with, for the fire and rescue service candidate a development of understanding of the investigative process, building on the techniques of examining, recording and reporting. To the pre-existing store of knowledge will be added a number of scientific subjects and further development of the overall understanding of fire behaviour, fuels, ignition sources, structural materials and furnishings. Key to the whole is the need to ensure that their methodology is able to withstand critical scrutiny by peers or a court. Police Crime Scene Managers/Investigators and others from outside the fire service may need to undertake some additional development programmes in order to acquire the underpinning knowledge of fire and fire behaviour required in order to interpret fire debris. All will need to become experts in the techniques of excavation, examination and analysis of information in order to reach the required level of expertise required for recognition as a competent investigator. Key to the Level 2 candidates’ development is the encouragement of a wider purview of the role of a fire investigation. It is essential that candidates recognise the need to examine all aspects of the event and not confine themselves to identifying simply a point of origin and cause. Fires are extremely complex events and many things combine to make a fire in one scenario behave in an entirely different manner to that in another scene which is essentially the same in terms of fire load, distribution of fuel packages and dimensions of compartments.

This graphic depiction of the information flow from sound Fire Investigation demonstrates the importance of taking a holistic approach. Each of the items shown can be further expanded to provide further sub headings and information trees.

The programmes devised to address the development needs of a Level 2 investigator must also take account of the levels of knowledge that may have been acquired by the candidate in the course of other training, career development programmes focussed upon fire fighting or command and control. There is a need to address the knowledge gaps which may occur in candidates who do not have a fire and rescue service background, and it is often necessary to assist FRS candidates to refocus and recognise the manner in which knowledge they hold which relates perhaps to fire extinguishment is essential in the interpretation of some of the data they have now to analyse in interpreting the fire damage they are examining. Typical examples are the indicators left by search and rescue teams, or where hose streams may have changed the patterns left by soot or flame movement. These programmes generally divide into two parts; theoretical and practical development and will cover broadly the following:

Legislation, authority, powers, duties, controls and restrictions, Smoke flame and heat movement and behaviour, Fire science including chemistry, physics and fire promoters and inhibitors, Electrical fault finding and contributors to initiation, Ignition sources and initiators, Toxicology of debris and health and safety assessment, Scene management, entry control and log books, Inter-agency working and sharing of information, Evidence gathering and controls, Pathology, DNA and techniques for identifying fatalities, Fingerprint and DNA evidence recovery and preservation, Information gathering through documents, interviews and other sources, Forensic scene examination including scientific methodology and the analysis process, Debris analysis, Pattern analysis and interpretation, Correlation of data, Recording activities, evidence and data through plans, photographs, notes and video etc., and Development of a hypothesis, testing and reviewing the same, and finally being able to write a report and defend their findings under cross examination in court.

Naturally the candidates will need to be given the opportunity to get their hands dirty in a physical scene examination or two as well. Again the mixture is very much a case of using lectures, demonstrations, table top exercises and as many practical scenes as possible (and economically sustainable!) into the mix. In this way the candidates get the benefit of lectures and practical sessions with acknowledged experts in all the disciplines involved in fire investigation.

Emphasis is also laid upon the need to avoid contamination of samples or scenes, particularly where a crew may have responded from another incident and may well have carried debris or traces of accelerants with them. The use of ever more sensitive instruments, and the sensitivity of a trained dog’s nose means that greater care than ever before is needed to ensure that the possibility of accidental contamination is reduced to a minimum.

At this level as well, candidates need to develop the ability to use as wide a range of research tools and sources as possible. While they may not be classed as “experts” in the fullest sense of the word, they do have an obligation to behave in as professional and expert a manner as their training, personal development and role allow. When in court, the judge may well decide to accept their expertise as being of a sufficiently high standard to recognise them as experts in that court and it is essential that they are able to support their arguments and opinions with a sound background of written reference or practical demonstration of experience. The training needs to include this element to ensure that every candidate, no matter what their background, has had the opportunity to develop these skills.

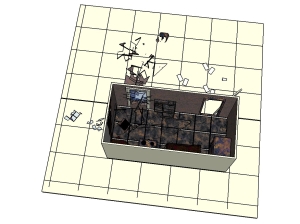

Realism in the setting of scenes is not a luxury, it is an essential tool if a realistic fire scene is to be achieved.

The practical work on any programme needs to be as realistic as possible, so the scenes built for training need to reflect reality as closely as possible. This, in its turn, presents the trainer with something of a challenge as they must attempt to “engineer” the fire scene in a manner that produces the evidence and the learning outcomes they want. There are several ways of doing this, one being to ensure that the fire is relatively carefully controlled by controlling the fuel packages present, the smoke and heat plume or simply by restricting the size of the fire or length of burn. Some trainers argue that it is not necessary to allow the compartment to go to full room involvement, others that to do so provides the students with a worthwhile challenge from which they stand to learn a great deal more. Either way, one aspect which does need to be addressed is the technique to be followed for an excavation – which sooner or later will be something an investigator will have to do!

The same scene as in the foregoing photograph – but post fire as the students see it.

Excavation skills are best acquired by actually carrying out this often laborious and sometimes thankless task. The tools required for it include “stepping plates”, trowels, sieves, protective clothing including dust masks and goggles and it is best approached in the same manner as an archaeologist approaching an ancient burial site. In some fire scenes there may also be a need to wear full enclosure coveralls to avoid DNA contamination, particularly where it may be a suspected murder scene.

Stepping plates are used to avoid destroying small items which may be vital evidence when first entering a room or compartment to be excavated.

By avoiding treading on the primary surface, an investigator can preserve any evidence that may be present if there is a need to reach a particular area before commencing a more detailed examination.

Part of the training for scene preservation is to develop an awareness of the need to employ a “Common Approach Path”, a route agreed between all agencies present to be used for all access and egress from a scene to avoid disturbing or destroying other evidence which may lie in areas adjacent to the scene or in areas which it is not intended to examine immediately. The use of the CAP must then be rigorously observed and enforced by the scene manager, who should also keep a strict log of everyone accessing or exiting the scene. This is particularly important in any scene where there has been a fatality or an explosion.

As ever, the recording of the data found, acquired or analysed must be done in a methodical and comprehensive manner. Note taking and keeping has to be done methodically and carefully, photographs logged and a record kept of precisely what each frame depicts. Plans need to be drawn to show where items were before recovery and to mark out the patterns left by the fire.

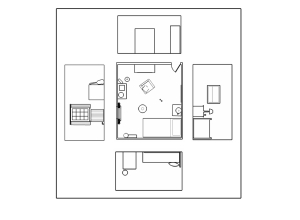

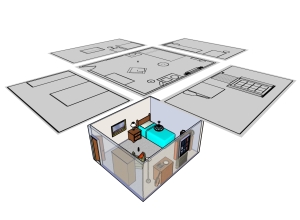

Archaeologists work to a grid reference and this is a useful technique in fire investigation as well.

Exploded views often help to show a contextual relationship between items of significance and the marks of burn or plume patterns on walls of furniture.

Naturally the development of the investigator has to make provision for the fact that he or she may well be faced with an explosion scene. There can be many causes of explosion, the most common in the UK, despite appearances in the media, is still the inappropriate use of gas, tampering with gas supplies or gas appliances or simply the accidental and undetected discharge of gas. Dispersed phase fuel air explosions will generally involve a wide range of specialists drawn from organisation such as the Health and Safety Executive, the Gas Supplier and the Forensic Science Services or similar private organisations such as the J H Burgoyne partnership. Usually the fire officer fire investigator is on the periphery of this, but may well hold vital knowledge which can contribute significantly to the investigation provided he or she has been adequately trained in this field. As already mentioned, joint working, shared information and agreed controls on entry, exit and the use of equipment and a common approach path become absolutely essential.

The shattering force of a relatively small device in a small car. This was the result of a commercially available “Shock Rocket” strapped to cement block and 2.5 litres of petrol mixed polyurethane foam. The quantity of explosive was about 70 grams of Flash Powder. (Photograph © P G Cox 2006)

For the fire officer understanding the mechanism of deflagrating or detonating explosions and the damage patterns likely to arise from each is a matter of some importance. Some air vapour mixtures, such as petrol or Propane, can produce blast forces close to those one would normally expect to see with the use of high explosive. Recognising the difference is not always easy, but it can be done if the investigator has been given the opportunity to develop the skill.

A backdraft seen head on – another form of fuel/air deflagration. Recognising the differences between this and other explosions is a skill developed through knowledge and experience. (Photograph © Dr-ing S Löffler 2005)

Increasingly the misuse of fireworks, pyrotechnics and other commercially available “low” explosives and incendiaries has created a need for training in this area of expertise, although it being highly specialised, it is generally handled by specialist teams. The terrorist threat in Europe and elsewhere has also increased the chances of an investigator finding himself or herself faced with peroxide based explosives and residues thus making it necessary that they are fully conversant with the risks these pose.

Maintenance of competence and currency is a problem for many fire officer investigators as the mobility of roles moves them from a role which includes fire and explosion investigation to one which does not. To this end short “refresher” courses have been developed which allow candidates to catch up on changes to legislation, renew skills or re-confirm their ability to investigate a fire. These programmes are structured to put in more practice and keep the theory to a level of “confirmation” or “refresher”.

One aspect which needs to be mentioned here, and which crosses the gap between a Level 2 and a Level 3 investigation, is the need to use engineering tools such as computer modelling in order to provide confirmation or support for a hypothesis. For many investigators this has become an essential tool, particularly when faced with analysing a fire event in a building of innovative design or which has apparently behaved in an unusual manner. Essential too, is an understanding of the interactions between various components of any “fire engineered” fire safety solution in a large structure, and it may be necessary for the investigator to analyse the effectiveness or otherwise of the systems – and their effect on the fire growth, spread and development.

Finally we have to deal with the Third Level of investigator, usually a forensic scientist of some years experience and very highly, if narrowly qualified in a particular field. The vast majority of those working at this level are in the private sector, having started out as graduate entrants and worked their way through a range of experience and further study usually culminating in a PhD, a course the vast majority of FRS investigators will never achieve. Their foundation knowledge is usually, but not exclusively developed in University and the focus of their development beyond graduation is in gaining the practical experience and credibility that goes with being recognised as a specialist “expert” in the field of forensic practice and investigation.

The recent introduction of a Register of Forensic Practitioners for Fire Investigation has seen a number of fire and rescue service personnel seeking to gain recognition at this level. This has generally been welcomed, but it does place a very heavy requirement on the fire and rescue service investigator who must now seek higher qualification alongside his or her experience in order to develop their knowledge base academically to achieve the level of knowledge a court expects of a person working at this level. Several universities have introduced Master of Science programmes in Forensic Science which include a fire and explosion investigation element and these have attracted a number of fire and rescue service officers who wish to expand their knowledge and skills into this field. Again this is a positive step since it can only benefit their employers in the longer term to have people capable of operating at this level.

Finally, it is important to appreciate that at all levels the training uses the concept of “Structured” investigation procedure to develop the professional abilities of all those who investigate fire or explosion scenes. Any person who embarks upon an investigation and does not follow the defined structural approach to fire investigation – as has been clearly shown by recent challenges to “expert” testimony in the US – is fundamentally failing to follow the simplest principles of sound investigation technique. It matters not whether it is likely to be subject to judicial proceedings or not, clearly the investigation is of value only if it is pursued and conducted with thoroughly professional vigour and a scientific process. Those who embark on an investigation with a preconceived notion of the outcome will find only the evidence that supports their particular conclusion.

The mind is like a parachute – it works best when it is open. Professional trainers in the UK do their utmost to ensure that those they are developing share that concept.

A Representation of the Structured Approach to Fire Investigation

Bibliography.

National Occupational Standards - Fire Investigation - Determine Origin, Cause and Development of Fire and/or Explosion; Office of the Deputy Prime Minister; 2005

NFPA 1033; National Fire Protection Association.

Posted by The Gray Monk at June 29, 2006 08:16 AM

Trackback Pings

TrackBack URL for this entry:

http://mt3.mu.nu/mt/mt-tb.cgi/4422